Oleh Dr. Reza Fahmi, M.A

Abstract

This research moves on from the fact that, the seeds of radicalism have developed in the city of Padang, in particular and West Sumatra in general. Where ppim research and also evidence of the handling of 16 suspected terrorists in the West Sumatra region, give an indication of this. However, the purpose of this study is among others: first, obtaining an overview of the perception of the community’s pattern of surau education that has been carried out for decades in the Minang Realm. Second, it provides a picture of people’s perception of radicalism in Padang City. Third, it describes the pattern of relationship between social education and radicalism that grows and develops in society. This study uses a quantitative approach. The population in this study was 256. Then using the formula Slovin, a sample of 160 people was obtained. The next data analysis technique used in this study is pearson correlation. The results of this study found (1) Based on the spread of min or average obtained an image that, people’s perception of social education is generally relatively positive. (2) In the spread of min or average of the behavior of radicalism according to the view of the community is relatively low or small. (3) There is a negative and significant relationship between people’s perceptions of social education and the behavior of radicalism among members of society. This means that the increase in positive perceptions in the community about social education, the lower the behavior of radicalism in the midst of society.

Keywords: Surau Education, Radicalism, Peace and Harmonization of Social Life

Introduction

The Center for Islamic and Community Studies (PPIM) UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta has released the results of the National Survey related to the religious religion of Muslim teachers on Tuesday, October 16, 2018. The activity, which was held at Le Meridien Hotel, Jakarta, took the theme “Dimming Pelita: Portrait of Indonesian Teacher Religiousness”[1]. The theme according to Fuad Jabali, Project Manager of CONVEY Indonesia, is very appropriate to describe the current religious condition of teachers. “This research was born from the realization that spaces in the world of education that should be open and dialogical are now increasingly closed because of narrow and intolerant understandings that negate diversity. Teachers who should be lampta in teaching the nation’s generation about tolerance and diversity, are now exposed to intolerance and radicalism,” fuad added. The release of the survey results was presented by Saiful Umam, Ph.D., Executive Director of PPIM Jakarta and Yunita Faela Nisa as the coordinator of the survey. Present as the instigator of Henny Supolo Sitepu, (Chairman of the Cahaya Guru Foundation), Heru Purnomo, (Secretary General of FSGI – Federation of Indonesian Teachers’ Unions), Bahrul Hayat, (Education Expert), and Jamhari Makruf (Advisory Board ppim UIN Jakarta).

This survey was conducted from August 6 to September 6, 2018 with muslim teacher analysis units from kindergarten / RA to high school / MA levels of all subjects. Methodologically, Yunita explained “the main variables to be explored are the level of intolerance and radicalism of the teacher, as well as the dominant factors that affect it. The sample of teachers was taken as many as 2237 with a margin of error of 2.07% and a confidence level of 95%” In the presentation of the survey findings, Saiful Umam stated that teachers in Indonesia ranging from kindergarten / RA to sma / MA levels have high intolerant and radical opinions. “In general, the percentage is already above 50% of teachers who have intolerant opinions. A total of 46.09% have a radical opinion. Whereas when viewed in terms of intentions-action, although smaller in value than opinions, but still the results are worrying. A total of 37.77% of teachers are intolerant and 41.26% are radical,” he said. Saiful explained, there are 3 dominant factors that affect the level of opinion and intentions of intolerance and radicalism of teachers. First, the Islamist view. As many as 40.36% of teachers agree that all science is already in the Quran, so there is no need to study western-sourced sciences. Both demographic factors, namely gender, madrasah vs. state schools, staffing status, income, and age. As a result, female teachers have more intolerant and radical opinions. Saiful added that “madrassa teachers are more intolerant than school teachers. This is influenced because in madrassas the environment is homogeneous. Teachers only teach Muslim students and interact with Muslim teachers only.” Still related to demographics, the survey findings also show that kindergarten/RA teachers are more intolerant of other religious people than teachers who teach at a higher level. In addition, teachers who earn less and those who teach in private schools also have the same tendency to intolerance.

Third, proximity to the organization and the source of Islamic knowledge. Data showed that 45.22% of teachers felt close to NU and Muhammadiah as much as 19.19%. Saiful added that “teachers who are close to NU and Muhammadiah tend to have more tolerant opinions and intentions than those who feel close to Islamic organizations that have been considered radicals”. Responding to the findings of this survey, according to Saiful “the government needs to expand programs that bring teachers together with other different groups so that the teacher experience is not homogeneous. It is important to improve teacher welfare by creating programs to increase teacher income. Furthermore, institutions that produce teachers need to empower non-UN subject teachers and private teachers without any distinction with subject teachers tested in UIN and state teachers” Responding to the results of the study, Bahrul Hayat saw that the religious attitude of teachers was strongly influenced by the closeness of identity (identity closeness). According to him, “how much teachers are exposed in interfaith disputes, this can be a determinant factor for teacher reasoning. We are now presented in a new narrative of massive social media. Abundant information related to hoaxes is a concern for all of us in forming teacher identity attachments” Finally, Jamhari Makruf stated that religious lessons and the school environment should make students inclusive. He thinks it is very dangerous if the teacher teaches something extreme and intolerant. “We have to look at the school because it seems to be no man’s land ,because the supervision of the school is weak. For example, there are studies that show that Rohis extracurriculars are not controlled activities. Radicalism and intolerance could be because of this no man’s land,” said the professor at the Faculty of Da’wah and Communication UIN.

As part of the national survey conducted, PPIM in collaboration with PPASB conducted a similar survey in West Sumatra. Where in this joint survey in West Sumatra, PPIM (Center for Islamic and Community Studies, UIN Jakarta) collaborated with PPASB (Center for Religious and Socio-Cultural Studies of UIN Imam Bonjol Padang) found that there were 33% of the 66 teachers involved in the study practicing intolerance that tends to be radical. This is the findings of the PPIM and PPSBA studies above which are widely questioned by academics and teachers involved in the dissemination of joint research results between PPIM (Center for Islamic and Community Studies, IIslam State University Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta) and PPSBA (Center for Religious and Socio-Cultural Studies, Imam Bonjol Padang State Islamic University), whose notes are both Islamic Universities in the country. The event took place at the Postgraduate Auditorium of Imam Bonjol State Islamic University (25/01/2019).

Thus, the above title is a simple conclusion from the findings of the PPIM and PPASB studies, this is a surprising thing for the people of West Sumatra in general and the cities of Padang and Payakumnuh which became the object of the study on “The Religious Attitude of School Teachers / Madrasahs in West Sumatra”. Of course, this result not only provides input to the government (Ministry of Education and Culture and the Ministry of Religion), which hierarchically carries out coaching on these teachers.

So it is not an exaggeration if among academics who are disturbed to want to know more about how the study mechanism is carried out. Then what methods are used as a tool for study analysis applied? There are even public figures who are clearly surprised and “reject” and question the truth or validity of the study carried out. This is the most rational reaction of the results of the study conducted, because scientific truth is not the same as public logic, which often contradicts between the two. [2]

Problems

The above joint research has substantial flaws in methodological aspects that are very fatal. These include: (1) Measuring attitudes according to the perspective of psychological science, not just measuring cognitive aspects. Thus ignoring two other psychological aspects, namely affective and psychomotor aspects. Thus we cannot ignore the psychoanalyst view initiated by Sigmun Freud who emphasized that attitudes are formed from three unsutr; knowledge (cognitive), feelings (affection) and psychomotor (behavior). This means that the study conducted ignores the psychological approach that becomes the “core” (center) of the study carried out. (2) Research involving only 66 people out of 80,000 teachers is a questionable solution of methodology. Where the size of the sample size (sample size) will affect the representation or representation of the population taken. How are the sample withdrawal provisions used to formulate the number of samples that are too small in a large population. (3) Random representation is indeed a step in accordance with the quantitative approach to ensure the fairness of respondents. Where each respondent has the same right to be selected as a respondent in the study. It’s just that the selected respondents have a high level of variance. There are public school teachers and religious schools as well as civil servant teachers and non-civil servant teachers. This is a problem that is difficult to draw conclusions, because each group of variance of research objects (respondents) is not divided. But it was taken for granted as a respondent involved in the research carried out. (4) Analyzing data with two different methods by drawing conclusions precisely becomes a problem in itself. Where a qualitative approach with guidance on interviews becomes a method of data collection. While the conclusion is generalized is a “chaotic” step of thinking in producing the final decision.

Ada two things that want to be underlined in this research article first, that research seeks to find the truth and not sensational and controversial justifications. Second, being a researcher must be independent and not only work to fulfill the wishes of donor institutions or sponsors, so that the expected results are useful for the community and not only produce scientific opinions, which is difficult to believe credibility, Do not corner Muslims because of their religious beliefs, but appreciate their existence as Citizens who also highly uphold tolerance and highly appreciate differences. Third, do not justify intolerance and radicalism because of their religion, but it is the perverted view of a few people that needs to be straightened out.

However, he does not want to argue on the vortex about the presence or absence of radicalism in the world of education in West Sumatra, but gives another side of the view about the development of Islam in West Sumatra which is ultimately expected to provide a comprehensive portrait of Islam that developed in the Minang Realm. So the problem in this study is that there is a relationship between social education and radicalism in Islamic education in West Sumatra?

Methodology

This study uses a quantitative approach. Where this study seeks to use pearson correlation statistical model to see the relationship between social education and radicalism in Islamic education in West Sumatra. This research seeks to explore public opinion, especially the city of Padang about surau education that has been carried out so far. A total of 265 people living in North Padang became a population in this study. They are people or citizens who have participated in surau education in their respective villages; Solok, Bukittinggi, Batusangkar, Pasaman, Pariaman and other areas in West Sumatra. This election is based on the consideration that, they are individuals who have experienced surau education in their home area and are now domiciled in padang city. Based on the formula Slovin found as many as 160 people by randomly selected . Sample withdrawal is done in simple random sampling (simple random), considering that the population has a clear sample framework, namely data from The Family Kart).

Results

Based on descriptive data obtained through research found, among others, are as follows:

Table 1

Respondent Categories By Age and Education Level

| No. | Category | Sum | Percentage |

| Age | |||

| 40 – 50 years old | 78 | 48,75 | |

| 51 – 60 Years | 82 | 51,25 | |

| Total | 160 People | 100,00 | |

| Education | |||

| Starata 1 (S-1) | 136 | 85,00 | |

| Strata 2 (S-2) | 18 | 11,25 | |

| Strata 3 (S-3) | 6 | 3,75 | |

| Total | 160 People | 100,00 |

Source: Research Results 2021

Based on the data in Table 1 above, it is obtained an illustration that generally respondents are between the ages of 51-60 years. As for their number as many as 82 people or equivalent to (51.25%). While respondents who are 40-50 years old as many as 78 people (48.75%). This suggests that in the perspective of developmental psychology can be categorized as intermediate adults. Where they have generally matured economically and socially, then have occupied certain positions in the midst of society.

Then based on the level of education, obtained the picture that the majority of respondents are educated undergraduate Bachelors (S-1). As for their number as many as 136 people or equivalent to 85%. Furthermore, the respondents who were educated starat 2 (S-2) as many as 18 people or equivalent to (11.25%). While the respondents who were educated Starata 3 (S-3) as many as 6 people or 3.75%). This means that, generally respondents have a good level of education, this is related to various education systems that have been applied in Indonesia[3]. As for what wants to be explained related to the education of surau (mosque) which is run in the people of Padang City with a Minang tribe, who live in West Sumatra, is to strongly emphasize the values of local wisdom that grow and develop in the community itself The presence of three main key leadership figures in West Sumatra “Tgigo Tungku Sejarangan”[4] supporting such a moral, valuable and civilized education. The components are: (1) Penghulu or Ninik Mamak, which provides guidance to children and nephews (nephews) to behave according to customary.[5] (2) Alum Ulama Islamic religious figures who provide a comprehensive understanding of Islam to the community[6]. and (3) Cadiak clever (smart people), who provide enlightenment to the development of science and technology[7]. On the other hand, there is an inseparable figure, it’s just that he is not an indigenous leader, it’s just given an honorable position in the community order, namely; Bundo Kandung (Mother) who becomes a role model (role model) for social life. The three components synergize in maintaining and improving the quality of society in indigo, norms and customs.

Initially, scholars understood more doctrinally to see the relationship between Islam and customs [traditions] in Malay-Indonesian communities, including Minangkabau. For example, Van den Berg with his concept: “reception in comflexu,” explaining that; “Customary norms are a filtering of sharia principles and norms, so customary norms are receptions of Islamic norms.” This concept was opposed by various experts in later times. They explained that the development of Islam in the Malay-Indonesian world gave birth to a new dynamic of Islam, namely the dynamics born from conflicts and accommodations between Islamic values and cultures with customs [local culture], thus giving birth to various new variants of Islam in the Malay-Indonesian world, which is also called “Local Islam,”[8]

Furthermore, the adherents of Islam in Minangkabau are very strong and obedient to hold firm philosophy. “Adat basandi syara’, syara’ basandi Kitabullah” (Customary law, law of the Qur’an) is a reflection of Minangkabau customs based on Islamic law. But even based on Islamic law, the Minangkau people are also very obedient and uphold customary law. This is where it can be seen how Islam and Adat unite in the community of Padang City, the majority of which are Minang.

Table 2

Spread of Min (Average) Public Perception about Surau Education

| No. | Category | Sum | Percentage |

| 1. | Positive | 139 | 86,87 |

| 2. | Negative | 21 | 13,13 |

| Total | 160 | 100,00 |

Source : Research Results 2021

Based on the data in Table 2 above, it is obtained that most respondents have a positive perception of education that is carried out, which is as many as 139 people or equivalent to 86.87%. While respondents who have a negative perception as many as 21 people or equivalent to 13.13%. This perspective is generally positive, more due to the teaching materials given, including: (1) Teaching the Quran (Tajwid and Tafsirnya). (2) Teaching the science of Fikih and Aqidah Akhlak. (3) The educational system uses halaqah (4) Teaching The Science of Order or Sufism (5) Teaching materials using the Yellow Book, (6) The Study of The Classics[9]. Therefore, they assume that the curriculum content contained in each subject matter is needed, as a living capital in behavior and adapting in society. Thus substantively the learning materials given to surau education do not come into direct contact with practical politics or the cultivation of certain ideologies to students.

Table 3

Spread of Min (Average) Perceptions About The Behavior of Radicalism

| No. | Category | Sum | Percentage |

| 1. | Tall | 4 | 2,50 |

| 2. | Low | 156 | 97,50 |

| Total | 160 | 100,00 |

Source : Research Results 2021

Based on Table 3, it is obtained that public perceptions of radicalism behavior are relatively low, which is only 156 respondents or equivalent to 97.50%. While generally respondents viewed that the behavior of radicalism is relatively high only 4 people or equivalent to 2.50%. This means that generally respondents view the behavior of radicalism in the midst of the people of Padang City, especially categorized as low.

This is supported by a study by BANPT (National Agency for Countermeasures) which found, “Based on the opinion of BNPT in 2017 showed that 39% of students in 15 provinces were interested in radicalism and Riau was included in the 15 areas studied. Some other provinces are West Java, Lampung, Banten, Southeast Sulawesi, and Central Kalimantan”. Of the 15 areas studied, Padang City did not include areas exposed to radical understanding.

Al Chaidar from Malikul Saleh University, Lhokseumawe, Aceh, said the number of students exposed to violent radicalism is very small in number.” Of all the data we have, it is out of sync with the data that BNPT has. It seems that the BNPT did not conduct research very seriously and as long as it accuses… So I think this is what should be accounted for for the results of their research and should be presented openly,” said terrorism observer Al Chaidar.[10]

The explanation above gives an idea that in the midst of society there is still an intense debate regarding the behavior of radicalism that exists in the midst of society. Given the BANPT study claims the number of radicalism behavior among the citizens of the community, while terrorism observers doubt the data revealed. This is where we believe that, the behavior of radicalism does exist in the community including in West Sumatra in general, especially in the city of Padang. It’s just that the aspect of the number of people involved is still not agreed (whether many or few). However, this study obtains an idea that people’s perception of radical behavior is still relatively low or slight. But what needs to be underlined is that the potential for radicalism in the midst of society needs to remain our common concern.

Table 4 Research Hypothesis

| Variable | Pearson Correlation | Sig |

| Perception of Surau Education and Behavior of Radicalism | -.640** | 0.000 |

Source: SPSS 20.0 for windows

Guided by Table 4 above, it is obtained that there is a significant negative relationship regarding people’s perceptions of social education and the behavior of radicalism. Where the more positive perceptions from the public about the education that followed, the weaker their perception of the behavior of radicalism in the community. This means that, people who receive education well then, they tend not to be spread on radical behavior. So this proves that a good understanding of Islam will be able to control society from radical behavior that they may be working on.

Discussion

Padang city is the largest city on the west coast of Sumatra Island as well as the capital of west Sumatra province, Indonesia. The city is the western gateway of Indonesia from the Indian Ocean. Padang has an area of 694.96 km² (https://www.padanginfo.com/2018/03/data-kota-padang.html). with geographical conditions bordered by the sea and surrounded by hills with a height of 1,853 meters above sea level. Based on data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) of Padang City in 2016, the city has a population of 902,413 people. Padang is the core city of the development of the Palapa metropolitan area. According to the local tambo, this city area was formerly part of the region established by Minangkabau nomads from the Minangkabau Highlands (darek). Their first settlement was a village on the southern outskirts of Batang Arau in what is now Seberang Padang. New villages were then opened to the north of the initial settlement, all of which included Kenagarian Padang in the Nan Dalapan Tribe customs; namely the Sumagek tribes (Chaniago Sumagek), Mandaliko (Chaniago Mandaliko), Panyalai (Chaniago Panyalai), and Jambak from Bodhi-Chaniago Alignment, as well as Sikumbang (Tanjung Sikumbang), Mansiang Hall (Tanjung Balai-Mansiang), Koto (Tanjung Piliang), and Malayu from Koto-Piliang District. There are also immigrants from other coastal regions, namely from Painan, Pasaman, and Tarusan. In the context of religious development in West Sumatra, there has long been practiced a pattern of surau education that is useful to equip the younger generation of soft skills and also the ability to exercise pencak silat. Even surau education also equips the younger generation in religious matters. It also provides us with knowledge that West Sumatra in general and padang city, especially about the attachment of local cultural customs to the values, methods and norms that grow and develop along with Islamic civilization. Where Islam is not only viewed as a religion, but also an ideal lifestyle and perspective in building a civilized Minang community.

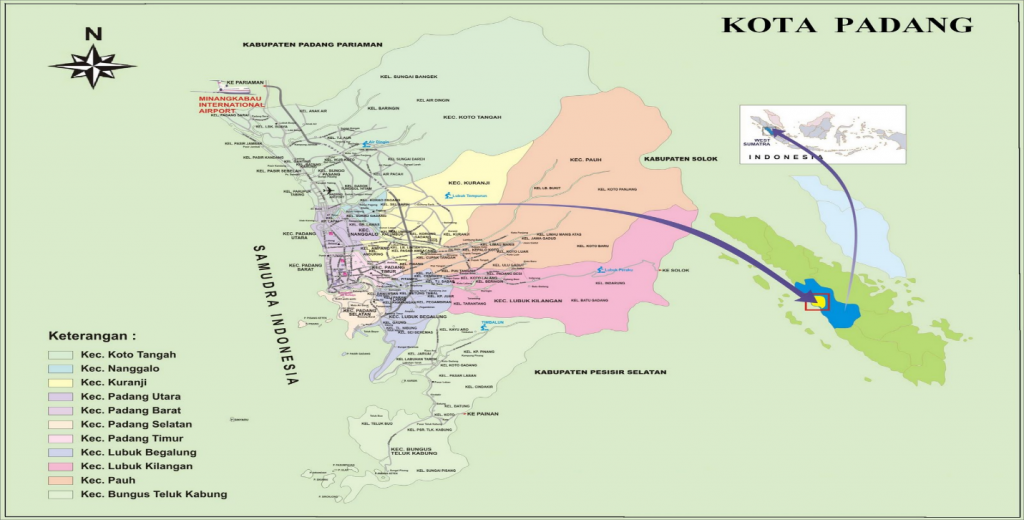

Therefore, surau education is the forerunner of the development of Islamic education that is rooted in local culture and wisdom in the midst of minang people. In addition, it also provides a unique educational pattern and is different from the pattern of pesantren education in Java as an example. Furthermore, in Figure 1 below is illustrated the location of the research based on the sub-districts in Padang City:

Picture: Research Location 2021 (Source: www.google-maps.com)

Furthermore, pada was originally used as a gathering place, rpat and bed for boys who have grown up, only when Islam came to Indonesia surau has a religious function and was first introduced by Sheikh Burhanuddin in Ulakan, Pariaman. Now surau has a function as a place to learn Islam, especially the order. As a traditional educational institution, surau uses the halaqah education system. The material taught is still about learning hijaiyah letters and reading the Quran, in addition to other Islamic sciences, such as faith, morals and worship.

In general, this education is carried out at night. In addition, it is also taught about the study of books where at this level the materials taught include sharaf and nahu science, fikih science, interpretation, and other sciences. The way to teach it is to read an Arabic book and then translated into Malay. After that, it was explained what he meant. [11] Surau education is often interpreted as a form of local wisdom. Local wisdom at the nagari level in West Sumatra is the foundation of the formation of the leadership soul in the area therefore its existence must continue to be preserved. “One of the lokal wisdom is education in surau (mushalla) belonging to the people or tribes. In addition to religious science, surau in West Sumatra also serves to provide martial arts and customary education. These two things are the foundation to build the spirit of leadership,” said Governor of West Sumatra Mahyeldi [12](https://www.harianhaluan.com/news/pr-101620717/pendidikan-di-surau-bentuk-kearifan-lokal-sumbar), while giving a speech at the Batagak Kudokudo Surau Lubuak Tajun event, The Sikumbang Datuak Putiah, in Jorong Sarang Crow, Nagari Pakandangan District Six Lingkung, Padang Pariaman Regency. According to him, by having a strong foundation, then the development of self-potential to become a leader will be easier when entering formal education to learn to organize. Currently not all people or tribes in Minangkabau still have surau. His role began to degrade, largely replaced by formal education in schools. Although in the mosque there is still religious education, but compared to the role of surau in the past, the position is not the same anymore. “During the struggle and the beginning of independence, historians note that there were about 2000 figures from Minangkabau who played a role at the national level. Indeed, it is the role of local wisdom at the nagari level that created it. Therefore, with the movement back to nagari, in fact it is also what wants to be resurrected,” he said.

This study supports several previous studies by Susanto (2018) which found that substantive religious education will promote radicalism in the name of religion. Likewise, research that has been conducted by Mukhlis (2018) which states that, Islamic religious education teachers are required to create a healthy religious climate to avoid radicalism in MA / SMA. One of the efforts that can be carried out by Islamic religious education teachers is to be able to practice deradicalization of Islamic education through integrating the values of anti-terrorism education in islamic religious education learning including citizenship, compassion, courtesy, fairness, moderation, respect for other, rsapect the creator, self control, and tolerance. Katakunci: Islamic Religious Education, Radicalism Introduction to Islamic Education is an education that aims to form a whole Muslim person, develop all human potential both physically and spiritually, fertilize the harmonious relationship of every person of Allah, man and the universe. Thus, Islamic education seeks to develop individuals as a whole, so it is natural to be able to understand the nature of Islamic education that departs from understanding the concept of human beings according to Islam. Thus it can be concluded that, Islamic education is anti-radicalism.

Research conducted by Sanaky and Safitri (2015) also provides knowledge about the education in the fight against radical behavior. It’s just that the important note in this study is that the cultivation of religious dogma needs to be a special concern, especially related to jihad. All of the above studies provide a comprehensive picture of education, especially religion contributes significantly to radical behavior.

Conclusion

An interesting note in this study include: (1) Islam as a religion has provided human guidance in behavior, so that Islamic signs contribute to the deviation of religious teachings> (2) Politicization of religion needs to be a common concern, because stigmatization of religion is a claim of truth over “heresy” in attracting confusion over the roots of radicalism in the name of religion. (3) Prejudice against Islam that precedes facts will give false conclusions, especially related to Islamic dogmas that bind its adherents. (4) Justification of absolute truth in the intra-religious relations of Islam by simply putting forward different propositions will actually give birth to misleading radical behavior. (5) Interfaith relations between Islam and Non-Islam need to be built with mutual trust and tolerance, so as not to prioritize competition, prejudice and intolerance.

Guided by the explanation above, it is necessary to understand that Islamic education should be built based on the local wisdom of each region in the country. Including surau education that has been carried out in a continuous manner from generation to generation. It is an educational root that combines Isla and customs as a form and pattern of Islam Nusantara that grows and develops on the water. So that the content of the curriculum built never instills intolerance, respects differences and upholds human honor as a form of dignity for humans according to the nature and drama they have. So it is impossible for us to assume it gives birth to radicalism in the midst of society.

The question that arises about “Quo Vadis” (where to go), the question of Islamic radicalism education in West Sumatra which became the initial question of the title of this article. It will only be able to be answered by whom and how do we view the dissolution of Islamic radicalism itself? Whether it will be brought to the “actor” or “understanding” instilled in the younger generation as an integral part of the terrorist behavior that often threatens and scares the community in the midst of poverty snares that they suffer themselves. Let the time of other research that will try to explain the problem in the future. (*)

References

Al-Qur’an al-Karim.

———–, (ed). Agama dan Perubahan Sosial. Jakarta: PT. Raja Grafindo Persada, 1996.

————, “Modernization in the Minangkabau World: West Sumatra in the Early Decades of the Twentieth Century”, dalam Claire Holt (ed), Culture and Politics in Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1972.

————, “Traditionalist and Islamist Pesantrens in Contemporary Indonesia” in Farish A. Noor, dkk (ed). Political Activism and Transnational Linkages (Leiden: Amsterdam University Press, 2007.

———–, Islam dan Masyarakat: Pantulan Sejarah Islam. Jakarta: Penerbit LP3ES, 1996.

———–, Schools and Politics: The Kaum Muda Movement in West Sumatera 1927-1933. New York: Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, 1971.

————, Sejarah dan Masyarakat, Lintasan Historis Islam di Indonesia. Jakarta, Pustaka Firdaus, 1987.

———–, Sejarah Lokal di Indonesia. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press, 1985.

……..,Menggapai Solidaritas Tensi antara Demokrasi Fundamentalisme dan Humanisme. Jakarta: Pustaka Panjimas, 2002.

………, Surau: Pendidikan Islam Tradisional dalam Transisi dan Modernisasi. Jakarta: Logos, 2003.

………,Jaringan Ulama Timur Tengah dan Kepulauan Nusantara Abad XVII & XVIII Akar Pembaruan Islam Indonesia. Jakarta: Kencana, 2007.

………,Konteks Berteologi di Indonesia Pengalaman Islam. Jakarta: Paramadina, 1999.

………,Pergolakan Politik Islam dari Fundamentalisme, Modernisme hingga Post-Modernisme. Jakarta: Paramadina, 1996.

………,Sebuah Pengantar dalam Tariq Ramadhan, Menjadi Modern bersama Islam: Islam, Barat, dan tantangan Modernitas. Bandung: Teraju, 2003.

………., Islam and State. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1987.

……….,dan Saiful Umam (eds), Tokoh dan Pemimpin Agama: Biografi Sosial-Intelektual. Jakarta: Litbang Depag RI dan PPIM, 1998.

……….,Renaisans Islam Asia Tenggara: Sejarah Wacana dan Kekuasaan. Jakarta: CV. Rosda, 1999.

………..,Islam and the Political Orderi. Washington, DC: CRVP, 1994.

………..,Selamatkan Islam dari Muslim Puritan. Terj. Helmi Mustafa. Jakarta: Serambi, 2006.

Abdul Razak, M. A., & Hisham, N. A. (2012). Islamic Psychology and the Call for Islamization of Modern Psychology. Journal of Islam in Asia, 9(1), 156–183.

Abdullah, M. Amin. Islamic Studies di Perguruan Tinggi: Pendekatan Integratif-Interkonektif. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar, 2006.

Abdullah, Taufik. Adat dan Islam: Suatu Tinjauan tentang Konflik di Minangkabau. Jakarta: Pustaka Firdaus, 1987.

Aberlee, David, F. “Catatan mengenai Teori Deprivasi Relatif” dalam Sylvia L. Thrupp, Gebrakan Kaum Mahdi. Bandung: Pustaka, 1984.

Abu-Raiya, H. (2012). Towards a systematic Qura’nic theory of personality. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15(3), 217–233.

Ahmed, Akbar S. Islam, Globalization, and Postmodernity. New York: Routledge, 1994.

al-Ashmawi, Muh}ammad Sa‘id. Usul al-Shari’ah. Kairo: al-Maktabah Madbuli al-Saghir, 1983.

Alfian dan Dewi Fortuna Anwar. “Wanita dalam Masyarakat Minangkabau”, dalam Kumpulan Naskah Simposium Pengaruh Adat Istiadat Minangkabau terhadap Kehidupan Wanita dalam Mengembangkan Budaya Bangsa. Jakarta: Panitia Penyelenggara Simposium Yayasan Bunda, 1973.

Algar, Hamid. Wahhabisme: Sebuah Tinjauan Kritis. Jakarta: Yayasan Abad Demokrasi, 2011.

Allen, James. 2007. “Aristotle on the Disciplihnes of Argument: Rhetoric, Dialectic, Analytic” In Rhetorica 25: 87–108.

Al-Saggaf, Yeslam dan Peter Simmons. 2015. Social media in Saudi Arabia: Exploring its use during two natural disasters. Technological Forecasting and Social Change Vol 95

Amiruddin, M. Hasbi, Konsep Negara Islam Menurut Fazlur Rahman. Yogyakarta: UII Press, 2000.

Ansary, Tamim. Dari Puncak Bagdad Sejarah Dunia Versi Islam. Terj. Yuliani Liputo. Jakarta: Zaman, 2010.

Arikunto, Suharsimi. Prosedur Penelitian: Suatu Pendekatan Praktik. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta, 1998.

Armstrong, Karen. The Battle for God. Terj. Satrio Wahono dan Abdullah Ali. Bandung: Mizan, 2001.

Arnold, TW. The Preaching of Islam. Delhi: Low Price Publication, 1990.

Ash’ari, Musa. Manusia Pembentuk Kebudayaan dalam Al-Qur’an. Yogyakarta: LESFI, 1992.

Asnan, Gusti. Kamus Sejarah Minangkabau. Padang: PPIM, 2003.

Awaad, R., & Ali, S. (2014). Obsessional Disorders in al-Balkhi′s 9th century treatise: Sustenance of the Body and Soul. Journal of Affective Disorders, 180, 185–189. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.003.

Awaad, R., & Ali, S. (2015). A modern conceptualization of phobia in al-Balkhi’s 9th century treatise: Sustenance of the Body and Soul. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 37, 89–93. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.11.003 .

Ayubi, Nazih N. Political Islam: Religion and Politics in the Arab World. London and New York: Routledge, 1993.

Azra, Azyumardi. “Globalization of Indonesian Muslims Discourse, Contemporary Religio-intellectual Connections Between Indonesia and the Middle East”, dalam Johan H. Meuleman (ed), Islam in the Era of Globalization, Muslim Attitudes Towards Modernity and Identity. Jakarta: INIS, 2001.

Badri, M. (1979). The dilemma of Muslim psychologists. London: MWH London. Badri, M. (2000). Contemplation: An Islamic Psychospiritual Study. Herndon, VA: The International Institute of Islamic Thought. Badri, M.B. (2013a, Oct). Psychological Reflections on Ismail al-Faruqi’s Life and Contributions. Paper presented at International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Bolland, B.J. Pergumulan Islam di Indonesia. Jakarta: Grafiti Press, 1985.

Bonab, B. G., & Koohsar, A. A. (2011). Reliance on God as a Core Construct of Islamic Psychology. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 216–220. doi:10.1016/ j.sbspro.2011.10.043 .

Bonab, B. G., Miner, M., & Proctor, M. T. (2013). Attachment to God in Islamic Spirituality. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 7(2), 77–105.

Bowie, Fiona. The Anthropology of Religion: An Introduction, 2nd edition. Blackwell: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Bruinessen, Martin van. Tarekat Naqsabandiyah di Indonesia. Bandung: Mizan, 1998.

Brummet, Barry. 2015. Rhetoric in Popular Culture, Fourth Edition. UK: Sage Publication Ltd

Bus, Yecki. Negara Kaum Assassin. Padang: Hayfa Press, 2012.

Cummings, Louise. 2007. Pragmatik, Sebuah Perspektif Multidisiplinere. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar

D, Ruben Brent dan Lea P Stewart. 2006. Communication and Human Behavior. United States: Allyn and Bacon

Datuk Radjo Panghoeloe, M. Rasjin Manggis. Minangkabau Sejarah Ringkas. Catatan Pribadi, tth.

Datuk Sangguno, Dirajo. Mustiko Adat Alam Minangkabau. Djakarta: Kementerian PP&K, 1955.

Daya, Burhanuddin. Gerakan Pembaharuan Islam: Kasus Sumatera Thawalib. Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana, 1995.

Dellong-Bas, Natana. Wahhabi Islam: from Revival and Reform to Global Jihad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. Eds. 2011. Handbook of qualitative research, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dobbin, Christine. Islamic Revivalism in a Changing Peasant Economy: Central Sumatra 1784-1847. London: Curzon Press, 1983.

Duke, James T. Conflict and Power in Social Life. Brigham: Brigham University Press, t.t.

Effendy, Bahtiar dan Hendro Prasetyo. Radikalisme Agama. Jakarta: PPIM-IAIN, 1998.

El Fadl, Khaled Abou. The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extrimism. San Francisco: Harper Collins Publishers, 2005.

Emmons, R. & Paloutzian, R. (2003). The Psychology of Religion. Published in Annual Review of Psychology 54:377–402.

Esposito, John L. Islamic Threat, Myth or Reality? New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Fahmi Reza and Aswirna Prima. The Relationships between Social Media Facebook and Family Divorce (Study in Middle – Class Society at Padang, West Sumatra-Indonesia) . Psychology and Education Journal.Vol.58.No.1. http://psychologyandeducation.net/pae/index.php/pae/article/view/1785

Fahmi Reza. Indonesia-China relationship: The political identity and social conflict in Padang, West Sumatera – Indonesia. Technium Social Sciences Journal. Vol. 13, 461-472, November 2020

Faisal Haji Othman,Islam Hadhari: Masalah Anjakan Paradigma Pemikiran Islam. (Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Information, 2004).

Fealy, Gerg dan Anthony Bubalo. Jejak Kafilah: Pengaruh Radikalisme Timur Tengah di Indonesia. Bandung: Mizan, kerjasama dengan Lowy Institute of International Policy, 2007.

Haeri, F. (1989). The Journey of the self. New York, NY: Harper San Francisco.

Hamid, R. (1977). Mandate for Muslim Mental Health Professionals: An Islamic Psychology. Proceedings of the first symposium on Islam and Psychology by the Association of Muslim Social Scientists pp. 1–7. St. Louis, MI.

Haque, A. (2004). Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists. Journal of Religion and Health, 43(4), 357–377. doi:10.1007/s10943-10004-4302-z.

Haque, A., & Keshavarzi, H. (2013). Integrating indigenous healing methods in therapy: Muslim beliefs and practices. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 7(3), 297–314. doi:10.1080/17542863.2013.794249.

Haque, A., Khan, F., Keshavarzi, H., & Rothman, A. E. (2016). Integrating Islamic Traditions in Modern Psychology: Research Trends in Last Ten Years. (2016). Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 10(1), 75–100. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0010.107.

Harris, K., Howell, D., & Spurgeon, D. (2018). Faith concepts in psychology: Three 30-year definitional content analyses. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, Vol 10(1), Feb 2018, 1–29.

Jurnal

Khalil, A. (2014). Contentment, Satisfaction and Good-Pleasure: Rida in Early Sufi Moral Psychology. Studies in Religion/Religious Sciences, 43(3), 371–389. doi:10.1177/0008429814538227.

Khan, S. H. (1996). Islamization of Knowledge: A case for Islamic Psychology. In M. G. Lodi, F. (2018). The HEART Method: Healthy Emotions Anchored in RasoolAllah’s Teachings: Cognitive Therapy Using Prophet Muhammad as a Psycho-Spiritual Exemplar. Chapter in York Al-Karam, C. Islamically Integrated Psychotherapy: Uniting Faith and Professional Practice. Templeton Press.

Koshravi, Z., & Bagheri, K. (2006). Towards an Islamic Psychology: An Introduction to Remove Theoretical Barriers. Alzahra University Psychological Studies, 1(4), 5–17.

Lunsford, Andrea A, Kirt H. Wilson dan R. Eberly (eds.) 2009. The SAGE Handbook of Rhetorical Studies. UK: Sage Publication Ltd.

M. Periasamy. Islam Hadhari: Prospect from a Non-Muslim Perspective. (Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Information, 2004).

McDaniel, S. (2016). Looking East in Monitor on Psychology. Vol 47, No.

Mohamed, Y. (1995). Fitrah and Its Bearing on the Principles of Psychology. The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences, 12(1), 1–18.

Mohamed, Y. (2009). Human Natural Disposition (Fitrah). In A. Haque & Y. Mohamed (Eds.), Psychology of Personality: Islamic Perspectives (pp. 3–18). Cengage Learning Asia.

Naupal. 2014. The Reconstruction Of The Role Of Islam In Indonesia As A Propethic Religion. Al-Ulum Volume 14 N0. 2, December 2014, Page 259-274

New Straits Times. Interview with Minster in the Prime Minister‟s Department (Religious Affairs) Datuk Prof. Dr. Abdullah Md. Zin, Kuala Lumpur, August 10, 2004.

Office of the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Web site: http://www.pmo.gov.my/ Diakses 12 Agustus 2018.

Paloutzian, R. & Park, C. (2005). Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality (first edition). NY: Guilford Press.

Paloutzian, R. & Park, C. (2013). Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality (second edition). NY: Guilford Press.

Qasqas, M. (2016). Sabr Therapy. Unpublished manuscript.

Ricklefs, M.C.. 2008. A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200. 4th Edition. UK: Palgrave Macmillan

Romzek, Barbara S. 2015. Living Accountability: Hot Rhetoric, Cool Theory, and Uneven Practice. dalam Political Science & Politics, Volume 48, Issue 01, January 2015, pp 27-34. American Political Science Association.

Rothman, A. & Coyle, A. (2018). Toward a Framework for Islamic Psychology and Psychotherapy: An Islamic Model of the Soul. Journal of Religion and Health. Springer: Vol 57, Issue 5. Pp. 1731–1744.

Rothman, A. (2018). An Islamic Theoretical Orientation to Psychotherapy in Islamically Integrated Psychotherapy: Uniting Faith and Professional Practice; York Al-Karam (editor). Pennsylvania: Templeton.

Safi, L.M. (1998). Islamization of Psychology: From Adaptation to Sublimation. The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences, 15(4), 117–126.

Saritoprak, S. & Exline, J. (2017). Spiritual Jihad: Implications for Struggle and Growth. Unpublished manuscript.

Shafii, M. (1985). Freedom from the self: Sufism, meditation, and psychotherapy. New York, NY: Human Sciences Press.

Siddiqui, B.B., & Malek, M. R. (1996). Islamic Psychology: Definition and Scope. In M. G. Husain (Ed.), Psychology and Society in Islamic Perspective. New Delhi, Indien: Institute of Objective Studies.

Skinner, R. (1989, July). Traditions, paradigms and basic concepts in Islamic psychology. Paper vorgestellt auf Theory and Practice of Islamic Psychology, London.

Smith, C. (2003). The Secular Revolution. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Speech by prime minister of Malaysia on occasion of the conferment of the honorary degree of doctorate of law by the International Islamic University Islamabad, Pakistan, February 17, 2005.

Speech by prime minister of Malaysia on occasion of the conferment of the honorary degree of doctorate of law by the International Islamic University Islamabad, Pakistan, February 17, 2005.

Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, UMNO Supreme Council,Kuala Lumpur, September 23, 2004.

Speech by Prime Minister of Malaysia, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, UMNO Supreme Council, Kuala Lumpur, September 23, 2004.

Utz, A. (2011). Psychology from the Islamic perspective. Riyadh: International Islamic Publishing House.

Vahab, A. A. (1996). An Introduction to Islamic Psychology. New Delhi: Institute of Objective Studies.

Zainal Abidin Bin Abdul Kadir,Islam Hadhari in Malaysia, (Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Information, 2004).

Zainal Abidin Bin Abdul Kadir, Islam Hadhari in Malaysia, (Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Information, 2004).

Thesis

Kurniawan Abdullah.2003. Gerakan Politik Islam Ekstraparlementer: Studi Kasus Hizbut Tahrír Indonesia. Tesis UI

Online

Al-Mustofa, Abdullah. 2015. Deklarasi Agama “Islam Nusantara”. Ditulis 8 Juni 2015, http://www.hidayatullah.com/ Diakses 11 Agustus 2018.

Djurai, Dhimam Abror. 2015. Perdebatan Atribut Islam Nusantara ala Jokowi. Ditulis 21 Juni 2015.http://www.jpnn.com/ Diakses 12 Agustus 2018.

Islam Hadhari: Concept and Prospect | Request PDF. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/ [accessed Aug 24 2018].

Office of the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Website: http://www.pmo.gov.my/ Diakses 12 Agustus 2018.

http://www.nu.or.id/ Diakses 12 Agustus 2018.

http://www.nu.or.id/ Diakses 9 Agustus 2018.

http://digilib.uinsby.ac.id / Diakses 4 Agustus 2018.

http://hizbut-tahrir.or.id/ Diakses 15 Agustus 2018.

http://hizbut-tahrir.or.id/ Diakses 14 Agustus 2018.

http://hizbut-tahrir.or.id/ Diakses 2 Agustus 2018.

http://hizbut-tahrir.or.id/ Diakses 12 Agustus 2018.

http://www.nu.or.id/ Diakses 8 Agustus 2018.

http://www.nu.or.id/ Diakses 10 Agustus 2018.

https://www.researchgate.net/ Diakses 12 Agustus 2018.

Office of the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Web site: http://www.pmo.gov.my/ Diakses 22 Agustus 2018.

[1]https://nasional.tempo.co/Diakses 01/26/2019.

[2] Densus 88 Anti-Terror Police arrested 16 suspected terrorists in the West Sumatra (West Sumatra) region on Friday (25/3). The suspected terrorists were from the Islamic State of Indonesia (NII) network. “They are NII networks,” said Karo Penmas Division of Public Relations Police Brig. Gen. Ahmad Ramadhan when asked for confirmation, Sunday (27/3/2022). Read the article detiknews, “16 Suspected Terrorists Arrested densus 88 in Sumbar NETWORK NII” more https://news.detik.com/berita/d-6003853/16-tersangka-teroris-yang-ditangkap-densus-88-di-sumbar-jaringan- Separately, The Head of Operation Assistance Densus 88 Kombes Aswin Siregar revealed the role of the suspected terrorists. There are those who play a role in the field of recruitment to military-style training.

Read the article detiknews, “16 Suspected Terrorists Arrested densus 88 in Sumbar NETWORK NII”. This information is very horrendous for the people in West Sumatra, because until now there are pros and cons about the existence of radicalism in the Minang Domain which is categorized as-SBK (Adaik Ba Sandi Syariat and Sharia Bersedni Kitabullah or customs based on religion (Islam) and Islam based on the Kitabullah (Qur’an and Sunnah).

[3] Some systems that have been implemented in the country, among others, (1) Open education system, this education system encourages students to increase creativity, innovation, and work skills there with classmates. In an open system, students become the core of the teaching and learning program. Learners are trained to be independent in being responsible and take the initiative to manage the learning process. (2) Students are required to measure their own desired and needed performance. Then, students can choose materials, places, times, and how to learn actively and independently. (3) The education system is diverse, this country has a diversity of languages and cultures. Therefore, an education system is created that can adjust to the wealth of the nation. As for the types of levels that can be selected, namely formal, non-formal, and informal. (4) Education system with value orientation, this one education system is enforced from the basic level. The students are given character education, such as discipline, responsibility, grace, and honesty. Lessons related to character values can be found in kindergarten lessons, even at the higher and secondary education levels. (5) Efficient education system in timing, In Teaching and Learning Activities (KBM), time management has been carefully considered so that students do not feel burdened with the subject matter delivered. In addition, the absorption of materials is more effective and efficient because the time given is not too short or too long. Students will also be more excited in studying. (6) Education system according to the changing times, Indonesia is always dynamic aka changing from time to time. It takes the right curriculum to adjust every situation and condition. One curriculum that is the result of changing times is the 2013 curriculum. (What are the Advantages and Disadvantages? (mutuinstitute.com)

This curriculum refines and revises the Education Unit Level Curriculum (KTSP) 2006. In addition to balancing education with the times, curriculum changes also aim to evaluate teaching staff and improve infrastructure.

[4] Tigo furnace only is a term Leadership at Minangkabau What is needed to regulate the government and norms that exist in society. The tigo furnace of the course consists of penghulu (niniak mamak), alim ulamaand clever clever (clever cadiakEach has a different role that is useful for organizing and building the lives of citizens. Minang.

[5] Penghulu or niniak mamak be leader Customs chosen for generations. Choosing a penghulu must be in accordance with the rules in the event of the appointment of the penghulu. As niniak mamak which protects nephew. and solve the problems that exist in his country because he understands about philosophy custom. One can be a master if he has a wise and wise soul. Penghulu has a degree when he is in office

[6] Alim ulama is a person in society who knows everything about science. religion. Alim ulama has the task of teaching religious education and spreading da’wah accordingly. Qur’an and Hadith teachings from the Prophet SAW, as well as exemplifying good behavior according to the teachings of the creed. Another task of alim ulama is to assist in some activities such as weddings. Currently alim ulama known as ustad / kiyai

[7] Clever clever or clever cadiak have a position at the same level as alim ulama and penghulu because they have extensive general knowledge. Clever clever can provide solutions in solving problems in the community environment. Clever is good at the task of making rules to organize, create security and tranquility, for a better life. In the present, groups of youth and thinkers are referred to as clever clever. (https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/).

[8] Fathurrahman, stated that local Islam is the result of the contribution of the local community in enriching the mosaic of Islamic culture and the creative form of a society to understand and translate Islam in accordance with their culture (https://kumparan.com/). The formation of local Islamic patterns cannot be separated from history. The spread of Islam in the Malay-Indonesian world involving many Sufi figures rather than fiqh, Sufism factors strengthen the spread of Islam in this region, due to the ability of Sufis to present Islam in activive packaging, especially by emphasizing conformity with Islam or contuinity, rather than changes in local religious beliefs and practices. As a result, the Sufi worldview became the main means of introducing the concept of Islamic beliefs to the indigenous peoples. With a strong tendency of mysticism in sufi ideas about religion, the loose approach to the local belief system and traditions (adat) is spread, so that it is natural to actualize the religious diversity of indonesian Malay communities, more referring to the local Islamic tradition, which gives birth to the interwovenness of indigenous local teachings with Islam as a universal teaching or in other words, form the domestication of Islam. The interweaving of customs and Islam among the minangkabau people has also begun since the minangkabau people accepted Islam as their religion, namely since the establishment of the Pagaruyung kingdom in the 16th century AD, which gave rise to a system of three kings, King of Nature (king of the world), King of Adat (king of customary law), and King of Worship (king of Islam), the interweaving of Islam with this custom runs gradually, along with the spread of Islam in Minangkabau, that is from the coastal area (region) to the hinterland (darek), which in minangkabau vocabulary is mentioned as; “Syara’ Mandaki, Manurun Customs.”.

[9] Syamsul Nizar, History of Islamic Education: Tracing the History of Education of the Prophet’s Era to Indonesia, 2nd cet, (Jakarta: Pranada media 2008).

[10] https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/indonesia-44357353. Retrieved 06 April 2022.

[11] https://waktungampus.blogspot.com/2014/09/persamaan-dan-perbedaan-pendidikan.html Accessed 06/04/2022.

[12] Local wisdom is the identity or cultural personality of a nation that causes the nation to be able to absorb, even process cultures that come from outside / other nations into their own character and abilities. Read more in the article “Understanding Local Wisdom: Its Functions, Characteristics, and Characteristics”, https://tirto.id/pengertian-kearifan-lokal-fungsi-karakteristik-dan-ciri-cirinya-f9mi. Local wisdom is also a hallmark of ethics and cultural values in local communities that are passed down from generation to generation. In Indonesia, Awareness of local wisdom began to flourish after the fall of President Suharto’s regime in 1998.. Furthermore, local wisdom is also defined as the ability to adapt, organize, and cultivate the influence of nature. as well as other cultures that are the driving force of the transformation and creation of Indonesia’s extraordinary cultural diversity. It can also be a form of knowledge, belief, understanding or perception along with customary customs or ethics that guide human behavior in ecological and systemic life. The values rooted in a culture are definitely not concrete material objects, but tend to be a kind of guideline for human behavior. In that sense, to study it we must pay attention to how humans act in local contexts. Under normal circumstances, people’s behavior is revealed within the boundaries of norms, etiquette, and laws related to a particular region. However, in certain situations where the culture faces challenges from within or from the outside, a response in the form of a reaction may occur. Responses and challenges are normal ways to see how change occurs in culture. Social structures and values, as well as local manners, norms and laws will change according to the needs of the social situation. Challenges in a culture can occur because of the feedback that occurs in the life network of a social system. This indicates the ongoing autopoesis which signifies that a social system in a culture regulates itself, a sign that a society can be said to be a living system. It is in the face of this change that local wisdom plays its role and function. Here’s a look at the functions, carkateristics, and characteristics of local wisdom. The characteristics of local wisdom must combine the knowledge of virtue that teaches people about ethics and moral values; Local wisdom should teach people to love nature, not to destroy it; Local wisdom must come from older members of the community; Local wisdom can take the form of values, norms, ethics, beliefs, customs, customs, special rules. Characteristics of local wisdom Able to survive in the midst of an increasingly massive onslaught of outside culture Has the ability to provide something to meet the needs of elements from outside culture Has the ability to merge or intermingleage of outside cultural elements into the original culture. Have the ability to control, give direction to the development of culture.